Scaling up fermentation processes represents one of the most challenging tasks in biochemical engineering. Moving from laboratory-scale experiments to industrial production requires careful planning and execution. This transition involves multiple variables that can significantly impact product yield and quality. Understanding fermentation kinetics at different scales is essential for successful bioprocess development.

Understanding Fermentation Kinetics Fundamentals

Fermentation kinetics describes the rates at which microorganisms grow and produce desired compounds. These rates depend on several factors including nutrient availability, temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels. Therefore, engineers must monitor these parameters continuously throughout the process.

The relationship between substrate consumption and product formation follows specific mathematical models. These models help predict how organisms will behave under different conditions. Additionally, they provide valuable insights for optimization strategies during scale-up operations.

Cell growth typically follows distinct phases: lag, exponential, stationary, and death phases. Each phase has unique characteristics that influence overall process performance. Consequently, understanding these patterns becomes crucial for timing interventions and maximizing productivity.

Key Challenges in Fermentation Scale-Up

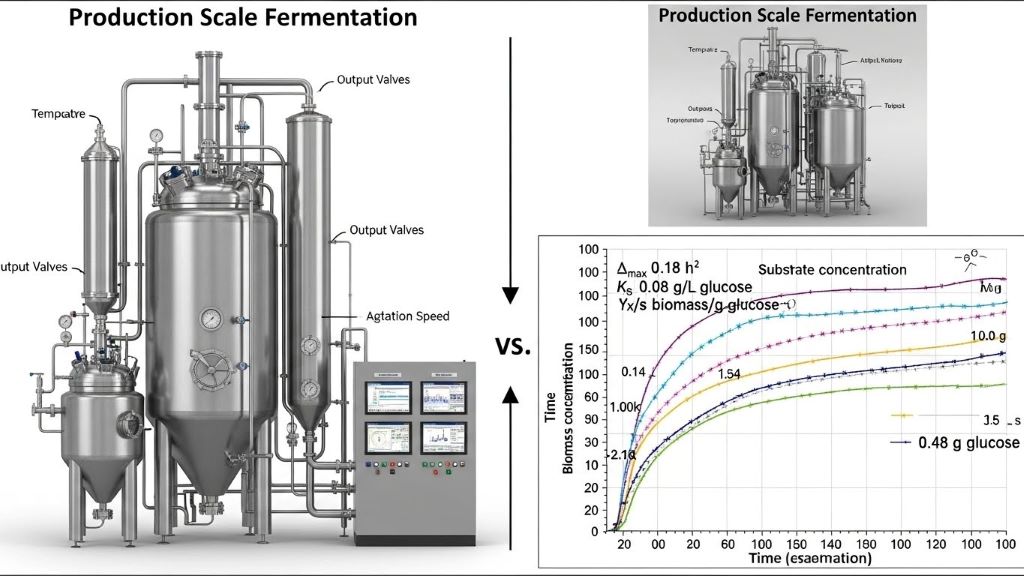

The transition from bench scale to production scale introduces numerous complications. Mass transfer limitations often emerge as vessel sizes increase dramatically. Oxygen transfer becomes particularly problematic because larger volumes create longer diffusion pathways.

Mixing efficiency decreases in larger bioreactors despite increased agitation power. This creates concentration gradients that microorganisms experience differently than in small vessels. However, these gradients can affect cell metabolism and product quality significantly.

Heat removal presents another significant challenge during scale-up operations. Metabolic heat generation increases proportionally with culture volume. Moreover, the surface area to volume ratio decreases, making temperature control more difficult.

Shear stress on cells changes with vessel geometry and impeller design. High shear rates can damage sensitive microorganisms or disrupt cellular structures. Therefore, engineers must balance mixing requirements with cell viability considerations.

Establishing Scale-Up Criteria

Successful scale-up requires identifying which parameters to keep constant across different scales. Common approaches include maintaining constant power input per volume, tip speed, or oxygen transfer rate. Each strategy has advantages depending on the specific fermentation characteristics.

The geometric similarity approach maintains constant vessel proportions across scales. This method preserves flow patterns and mixing characteristics reasonably well. Nevertheless, perfect similarity becomes impossible due to physical constraints and equipment limitations.

Dimensionless numbers help engineers predict behavior across scales mathematically. Reynolds number characterizes flow regime, while Sherwood number describes mass transfer efficiency. Additionally, the Damköhler number relates reaction rates to mass transfer rates.

According to research published in Nature Biotechnology, oxygen transfer coefficient serves as a critical scale-up parameter for aerobic fermentations. This parameter directly influences cell growth and product formation rates.

Step-by-Step Scale-Up Strategy

Begin with comprehensive characterization at laboratory scale using controlled bioreactors. Document all critical process parameters including agitation speed, aeration rate, and feeding strategies. This baseline data becomes invaluable for troubleshooting larger-scale operations.

Progress through intermediate pilot scales before jumping to full production volumes. Pilot-scale studies reveal problems that laboratory experiments cannot predict. Furthermore, they provide opportunities to refine control strategies without risking expensive production batches.

Install adequate instrumentation for monitoring key variables in real-time. Modern sensors enable continuous tracking of dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, and biomass concentration. Consequently, operators can respond quickly to deviations from optimal conditions.

Develop robust feeding strategies that accommodate larger working volumes. Fed-batch and continuous feeding modes often work better than simple batch operations. These approaches help maintain optimal substrate concentrations throughout the fermentation cycle.

Safety Considerations During Scale-Up

Safety must remain the top priority when working with larger fermentation volumes. Increased quantities of flammable solvents, toxic metabolites, or pathogenic organisms raise risk levels substantially. Therefore, comprehensive hazard assessments should precede any scale-up activities.

Containment systems require careful design to prevent releases of biological materials. Pressure relief systems, sterile barriers, and emergency shutdown procedures protect personnel and environment. Additionally, regular maintenance ensures these safety systems function properly when needed.

Sterilization procedures become more challenging at larger scales. Longer heating and cooling times may expose media components to degradation. However, validation studies confirm that all vessel areas reach adequate sterilization temperatures.

Personnel training becomes increasingly important as process complexity grows. Operators must understand fermentation kinetics and recognize signs of process deviation. Moreover, they need clear protocols for responding to various emergency scenarios.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration provides comprehensive guidelines for safe handling of biological materials in industrial settings. These regulations cover facility design, personal protective equipment, and waste disposal procedures.

Optimizing Mass Transfer at Large Scale

Oxygen transfer often limits aerobic fermentation productivity at industrial scale. Engineers can improve transfer rates by increasing agitation speed or air flow. Nevertheless, excessive agitation may cause foam formation or cell damage.

Sparger design significantly influences bubble size distribution and gas-liquid interfacial area. Fine bubbles provide more surface area but may coalesce quickly in large vessels. Conversely, larger bubbles have less surface area but better stability.

Alternative oxygenation methods include oxygen-enriched air or pure oxygen supplementation. These approaches increase driving force for oxygen transfer without additional agitation. However, they require careful monitoring to prevent oxygen toxicity.

Computational fluid dynamics modeling helps predict mixing patterns and dead zones. These simulations guide impeller placement and baffle design before expensive fabrication begins. Additionally, they identify regions where cells might experience suboptimal conditions.

Monitoring and Control Systems

Advanced process analytical technology enables real-time monitoring of critical quality attributes. Spectroscopic methods measure metabolite concentrations without sampling delays or contamination risks. This immediate feedback allows precise control of feeding and environmental parameters.

Automated control systems maintain optimal conditions despite disturbances and variations. Proportional-integral-derivative controllers adjust inputs based on measured outputs continuously. Furthermore, model predictive control anticipates future states and makes proactive adjustments.

Data logging creates permanent records for regulatory compliance and process improvement. Trending analysis reveals subtle changes that might indicate equipment degradation or raw material variations. Therefore, historical data becomes a valuable resource for troubleshooting production problems.

Validation and Documentation

Regulatory agencies require extensive validation before approving scaled-up bioprocesses for commercial production. Consistency studies demonstrate that multiple batches meet quality specifications reliably. This documentation proves the process operates in a state of control.

Standard operating procedures must be detailed enough for consistent execution by different operators. These documents include equipment settings, sampling schedules, and acceptance criteria for each process stage. Moreover, they specify corrective actions when parameters drift outside normal ranges.

Technology transfer from development to manufacturing requires clear communication of critical knowledge. Process understanding documents explain why certain parameters matter and how they interact. This prevents loss of institutional knowledge when personnel change.

Conclusion

Scaling up fermentation processes safely requires systematic planning and thorough understanding of kinetic principles. Engineers must address challenges related to mass transfer, mixing, heat removal, and shear stress carefully. By progressing through intermediate scales and maintaining robust monitoring systems, manufacturers can achieve reliable production at industrial volumes. Safety considerations, proper validation, and comprehensive documentation ensure regulatory compliance and protect personnel. With attention to these critical factors, biochemical engineers can successfully translate laboratory discoveries into commercial reality.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common reason fermentation scale-up fails?

Inadequate oxygen transfer represents the most frequent cause of scale-up failure in aerobic fermentations. As vessel size increases, maintaining sufficient dissolved oxygen becomes increasingly difficult. This limitation can dramatically reduce cell growth rates and product yields compared to laboratory-scale results.

How long does the fermentation scale-up process typically take?

The complete scale-up process from laboratory to commercial production typically requires two to five years. This timeline includes pilot-scale studies, optimization experiments, validation batches, and regulatory approval processes. Complex products or novel organisms may require additional time for thorough characterization.

What scale-up ratio should be used between successive fermentation stages?

Most engineers recommend scale-up ratios between 5:1 and 10:1 for successive stages. Smaller ratios provide more data points but increase development time and costs. Larger jumps risk encountering unexpected problems that are expensive to solve at bigger scales.

Do all fermentation parameters need to remain constant during scale-up?

No, maintaining all parameters constant across scales is neither possible nor necessary. Engineers select one or two critical parameters to keep constant, such as oxygen transfer rate or mixing time. Other parameters adjust naturally to maintain the chosen constant values.

How can I minimize foam formation in large-scale fermenters?

Foam control strategies include mechanical foam breakers, antifoam agents, and optimized aeration rates. Selecting appropriate surfactant concentrations in media formulations also helps. Additionally, controlling agitation speed and air flow rate prevents excessive foam generation initially.

Related Topics:

Everything you need to know about Biomedical Engineering

Leave a Reply